Bryn Athyn Cathedral: The Building of a Church

E. Bruce Glenn

The Stained Glass

THE ACHIEVEMENT of the stained glass windows in the Bryn Athyn Cathedral is hard to exaggerate. The reasons for this are numerous; chief among them is the fact that this feature of the church employs a material made by man in distinction from those taken directly from nature. All of them, of course, are gifts from the hand of God; but the stained glass required the composing skill and imagination of men to produce the substance out of which the windows were fashioned. Furthermore, this accomplishment, to be consonant with the principles and results of the Cathedral as a whole, had to be started anew, after a lapse of hundreds of years. The high art of making stained glass, in the full sense of the term, had wellnigh vanished by the seventeenth century. Moreover, its use in religious architecture had degenerated two hundred years earlier, with the advent of pictorial realism under the impact of Renaissance painters and the consequent separation of the stained glass windows from the architectural and artistic harmony of the church as a whole.

This, of course, is an expression of viewpoint rather than a statement of fact. There are those who defend the naturalistic style of later stained glass design as preferable to what they term the archaism of the medieval work. This is not the place to debate the question. Two points may be made, however. First, from the standpoint of religious symbolism, the depiction of biblical personages calls for a conventionalized or monumental presentation. These figures and their stories are far from the level of our daily intercourse, as the books through which we learn of them are set apart from ordinary human uses of language, even the most artistic. They should be seen thus, not for their own sake as pictures, but for the meaning that shines through them, as the sun glows through their colors.

Even as art, apart from religious purpose, the windows of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries have been hailed as the supreme achievements in the art of stained glass. By universal consent, Chartres leads the great list; but the list is long, and only begins with such names as Canterbury, Bourges, and Rouen. From that day until now, nothing has been created to replace the true religious aesthetic that made those windows the highest symbolic art of Christianity.

The problem facing the builders at Bryn Athyn was an awesome one; to design windows of equal artistic integrity to reflect in symbolic form the doctrines of a new Christianity; and to make glass worthy of its use. Raymond Pitcairn, carefully studying the medieval glass, early realized that use of ready-made glass would result in failure, because of its essentially different form and inferior quality. As a recent encyclopedia article notes, "In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the old technique disappeared, and the art of stained glass was virtually dead." Yet the same article concludes, "The technical and material resources of the art are greater than they have ever been. All that is lacking is the desire; and to foster this we cannot do better than instill a wider consciousness of the unique and unrivalled beauties of the art as it existed in the past."

At Bryn Athyn the desire was not lacking—not simply as impetus to artistic emulation, though this was to serve as means; but in the ardent hope of creating windows that would imbue with renewed color and meaning a house of worship. As for the old technique that had disappeared, this was the making of glass from "pot metal," the melting of the colors into the glass itself as it was formed, by various metallic oxides—a practice replaced in modern times by the enameling of pigments onto clear glass. A return to the making of pot metal glass was called for, but not for the sake of imitating the medieval artisan. Rather it was to arrive as closely as possible to his unrivalled colors and tones, beside which the later glass appears muddy, garish, or pale.

The audacity of such an endeavor was apparent. Yet the way had been paved by the establishment of shops for stone and wood work, under the principles of perseverance and the taking of pains. As Lawrence Saint, one of the window designers, later expressed it, "Research, endless studies, experimentation, were the means used to obtain superior results."

Translations were made and carefully read, of Theophilus, a recorder, and Viollet-le-duc, an historian, of medieval glass-making. Trip after trip after trip was made to study at close hand a splendid collection of medieval glass gathered by Henry C. Lawrence, a New York broker, and set up in his home, as well as other pieces in the Metropolitan Museum. Lawrence's gracious interest and hospitality were beyond the ordinary. When his collection was sold in 1921, following his death, Raymond Pitcairn obtained some of the most beautiful panels of stained glass existing outside the great cathedrals; and his artists and glassmakers worked in the presence of these inspiring models. He sent his window designers to Europe to see the work of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries in place, to take photographs and make detailed drawings. Yet the biggest challenge to success lay in experimentation, the actual making of the glass.

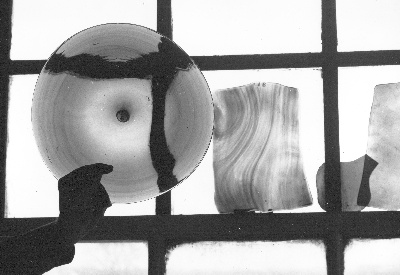

A disk, or roundel, of stained glass still adhering to the blowpipe. The contours and variations in thickness, that distort the window frame behind, are part of the glory of this glass in transmitting the sunlight into the church. This piece is probably violet, yellow, or light green. Click on image for a larger version.

The "glory hole," opening into a white-hot furnace where the blower's pipe held the globule of glass. The air in the glass shop was dry and intense—and exciting in the presence of this new-old art. Click on image for a larger version.

For this work Pitcairn turned in 1916 to a Swedish-born glassmaker on Long Island. John Larson, a master glass blower who learned the trade from his father, was also interested in the formulae for various types and colors of glass. Pitcairn persuaded him to experiment in the making of glass that would have both the beautiful colors of the medieval product, and also its variety of tone and texture that had resulted from the hand blowing and perhaps the crude tools of the medieval artisan. Here, once again, was an example of beauty achieved through the individual's limitations that were turned to benefits. Certainly the irregularities of thickness and inexactness of formula repetition were part of the glory with which the medieval windows translated the light, in sharp contrast to the dead monotone of a mechanically produced sheet.

The experiments went on for years, while Pitcairn sought to bring Larson to work at the Cathedral site. The glassmaker, who had succeeded by trial and error in matching much of the thirteenth century glass, finally came in 1922, and a glass shop was erected across the pike from the church. With him Larson brought another Swedish glass blower, David Smith, who had begun his trade in a lamp chimney factory at the age of six. "Davy," who combined intensity of effort with a kind gentleness, lived to blow most of the glass used in the Cathedral, producing his last batch in 1942 at the age of seventy-eight.

A labor thus prolonged needs its apprentices to learn and carry on, even as in the Middle Ages. Such an apprentice in the glass shop was Ariel Gunther, a young New Church man of nineteen. Raymond Pitcairn asked him if he was interested in devoting his life to the work of making stained glass and mosaic. Gunther had no background in the field; but he plunged into the work with assiduity and imagination so that when Larson left in 1925, he was able, together with Smith, to take full responsibility for the glass production and carry it through to the essential completion of the Cathedral windows over a period of many years.

The first glass made in the new shop was produced directly in a small, crude furnace shaped out of fire-clay blocks. Later, crucibles were used to hold the pot metal, into which the various oxides were introduced—cobalt for the blue, manganese for the violet, copper for the green and also for the incredibly difficult striated ruby, the secret of which had been lost for centuries. Larson had made some progress with this last color, so important a part of the best thirteenth century glass, when he arrived in Bryn Athyn; but it remained brittle and hard to cut. Its tonal variations, finally achieved by Gunther with remarkable fidelity to the old glass, were the result of dipping a clear green-white sheet into a crucible of the copper mixture, from which process the striated color developed while the glass was being annealed. Experts who see the Bryn Athyn ruby in place find it hard to believe they are not looking at medieval glass.

Pot metal glass, ready for cutting and leading to fit the artist's conception. All the Bryn Athyn glass is "pot metal," the colors being introduced by metallic oxides into the molten glass rather than being enameled onto its surface later. Click on image for a larger version.

The cobalt blue, in varying shades, was also the result of long experimentation. A simple test devised to determine the comparative warmth or coolness of each batch was to view a match flame held back of it. The flame, verging from green to lavender, gave an accurate guide for altering the formula of the next batch. Indeed, the adding of a few grains of metallic oxide in a fifty-pound batch resulted in subtle variations of color; it is small wonder that the early experiments in crucibles holding three or four pounds of molten glass proved so difficult.

The making of the glass was a vivid experience. The air in the shop was dry and stifling from the intense heat of the furnaces, which had been fired well before dawn. At the "glory hole," the opening through which the blow pipe was manipulated, a glimpse could be caught of a globular mass of color at the tube's end, which melted and opened as it was brought near the flame. Then, dexterously, the blower twirled the pipe so that the open edges of the glass spread to form a disk, thicker at the center and with slight but important variations along the surface. Decades after the shop had been torn down, bits of colored glass could still be picked out of the gravel near the Academy's clay tennis courts, where the glass shop once stood.

A room in the garden house of the Pitcairn home, "Cairnwood," was used to store the sheets of glass. Here too the artists worked, designing the windows as well as painting the details of features and drapery and the delicate scrolls and hatches of the grisaille panels, which were then fired fast to the stained glass. There were several of these artists: Clement Heaton, an English glass-maker who, though he did no actual designs of windows placed in the church, contributed much of background and understanding of the art; Winfred Hyatt, a young member of the Bryn Athyn congregation who was engaged by Pitcairn in 1914 to begin work on the windows that were still years away, and who designed more of them than any other man, as well as painting the portraits of many of the church's leaders; Lawrence Saint, an articulate and pious man who later gained fame in other applications of a skill for which he paid tribute to Pitcairn as "a gracious and sensitive employer"; Rowland Murphy, a temperamental but imaginative Canadian; and Paul Froelich. These men had various perspectives, much like the tones and surfaces of the glass with which they worked; but like the glass, their contributions harmonized under the inspiration of the medieval example and the new religious ideal to which it was being adapted. The care with which their windows were designed and the glass selected, painted, and leaded into a whole, is exemplified by Saint's statement that in nearly eleven years of working at the Cathedral he completed six windows—three figures, two small roses, and one grisaille.

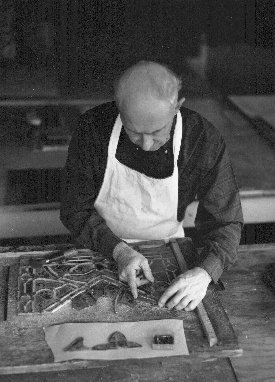

Here the glass, after details have been painted and fired upon its colors, is fitted into a panel with a simple leading instrument. Click on image for a larger version.

There are, to put it simply, three basic kinds of window design in the church proper: representative figures, comparatively large in scale and monumental in style; groups of medallions depicting biblical events; and grisaille, the ornamental windows of which the gray glass gives a pearl-like translucency.

All of the nave aisle windows are of grisaille, in geometric patterns outlined by brilliant bands of green, blue, red, and yellow glass, the motif of each window differing from all the others. Some are developed in a pattern of circles, others in lozenges and quatrefoils or combinations of these. Within and around these bright forms are tendrils of acanthus leaves and other conventional lines placed by the painter's brush. The gray whiteness of the glass is thus subdued, and the whole window is filled with depth and delicacy.

To inspire the artists to these productions, Pitcairn had obtained two grisaille panels of the thirteenth century. One of these was actually placed for many years as part of the westernmost window in the south aisle; and only from the pitting on the exterior surface could any but the most discerning eye pick it out from among its newly made fellows. As the eye travels eastward, the patterns become more free and individual.

The windows of representative figures are several. The most imposing is the great west window discussed in the second chapter, its tall figures symbolizing the five successive churches established by the Lord upon this earth. Another example is the pair that stand in the walls at the east end of the chancel aisles. In the north aisle is Moses, representing the revelation of the Old Testament, and on the south, the apostle John to represent the New Testament. These figures have the strength and dignity associated with the great age of the medieval glass, and appropriate to their importance in religious history. The borders of these two windows are particularly brilliant.

The three-light windows set in the nave clerestory are also of this character, each of their side lights setting forth a biblical figure of the Old Testament to whom God came in the form of an angel, as depicted in the central light. In the small panels below are depicted scenes from the story—of Adam, Noah, Joshua, Samuel, and others, ten in all.

The final type of window, a series of related medallions representing consecutive incidents from the Word, is found in the chancel clerestory and the south transept. The chancel windows, each having nine panels in three lights, recount the several incidents associated with the Lord's six visits to Jerusalem, from His presentation in the temple to His triumphal entry before the crucifixion and resurrection. The medallions are perforce small; and their combinations of various colors on this scale turn them into glowing gems, especially when the sun's rays fall directly on their panes.

This jewel-like quality is still more present in the lancet windows of the south transept. Here the individual pieces are even smaller, and the whole becomes a cascade vibrant with life and color. These are the prophetic windows. The pointed arch and three central medallions of each window depict in miniature various episodes from the four major prophets; and the half-circle medallions between these at the sides picture scenes from the minor prophets.

In the chapel, below the south transept, two windows of medallions are unique in depicting scenes from the Word as given through Swedenborg. Thus these windows complete the record begun in the nave and transept with representations from the Old Testament, and continued in the chancel by scenes from the New Testament. As part of his revelatory experience, Swedenborg witnessed many events in the spiritual world; some of these took form as consecutive episodes in the life of angels and spirits, or as symbolic scenes reflecting doctrinal truths. Swedenborg reported them in several of his theological writings, and called them Memorabilia, or "Memorable Relations." These, the last windows set in the church, give opportunity for closer view than is afforded by the other pictorial windows.

We turn last to the great east window, that which is most steadily before the eyes of the congregation. At the top the Lord looks down as from His throne. Below Him are ranged the twelve disciples who followed Him on earth and whom He called together again to spread the Word of the New Revelation throughout the heavens. This window combines the glow and variety of the medallion style with the grandeur of the monumental. Its proportions, filling the east wall above the altar on which rests the Word, its mullions and simple tracery, give it the restraint needed in its place of prominence.

While this account has emphasized the beauty and artistic integrity of the stained glass, a full and separate treatment of the windows' religious representation, based on the doctrines of the New Christian Church, will be given in the next chapter. For in the windows, more than in any other detail or sequence of the structure, there was opportunity to present in pictorial form the Divinely given truths of faith that are the Church's foundation and guide.

Top | Previous Chapter: The Metal Work | Next Chapter: The Windows and Their Representations | Table of Contents