Bryn Athyn Cathedral: The Building of a Church

E. Bruce Glenn

The Stone Work

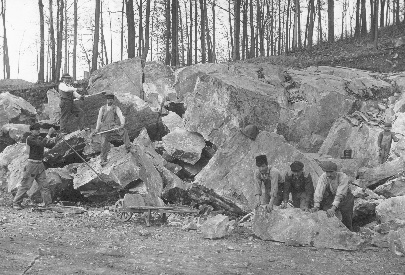

Bryn Athyn Quarry. One of the historical photographer's problems is the tendency of his subject to strike a pose. These men form an excellent composition; at other times they quarried quite a lot of fine metamorphosed granite. Click on image for a larger version.

STONE IS THE VERY FOUNDATION of the earth, associated with steadfastness and permanence. Frequently it is also thought of as cold and unyielding. Yet as manifested in the walls and cut stone of the Cathedral, it combines the sense of permanence with a grace of line, hand-worked texture, and variegation.

The causes of this united strength and grace are many. But before we examine the stone work more closely, the underlying spiritual principle of its quality may be stated.

This principle is set forth in the doctrine elucidated through Swedenborg by which the natural world is seen to be related to the spiritual as effect to its cause. The nature of this relationship is called "correspondence" in the Heavenly Doctrine of the New Church; and the doctrine of correspondence pervades the new revelation both in explanation of the Divine laws of creation, and in its exposition of the spiritual meaning of events and objects in the Old and New Testaments, all of them representative of doctrinal truths for the rational mind now opened by means of the sciences.

Stone, or rock, finds frequent and signal mention in the Word. The Ten Commandments, given on Sinai and kept in the Ark of the Tabernacle, were engraved on tables of stone. Altars and pillars of stone were raised to commemorate the Divine judgment and mercy. Indeed, the Lord calls Himself "the Rock of Israel" and, prophetically, "the Stone which the builders rejected" but which was to become "the head of the corner." And in exhorting men to found their lives upon His truth, He told the disciples, "Whosoever heareth these sayings of mine and doeth them, I will liken him unto a wise man who built his house upon a rock: and the rain descended and the floods came and the winds blew upon that house, and it fell not, for it was founded on a rock."

The foundations of man's life are the truths by which his mind grows to be truly human and which he puts to use in life's relationships. These truths begin as knowledges in the memory, loose and unproductive as the sand. But as the mind matures, these knowledges are compacted and given form and order by the heat and pressure of purpose, the mysterious chemistry of love, and are thus made a foundation for use.

So also were the rocky strata that underlie the continents formed out of the flowing minerals of the earth and in time established as strong stones; igneous granite, sedimentary sandstone and limestone, metamorphic gneiss. Of these and related stones, carefully sought out, lovingly shaped and placed, the Bryn Athyn Cathedral was built, as the Church of God is erected from the truths of revelation searched out and placed together for the purposes of life.

The varieties of stone set into the Cathedral as it grew may be seen at close hand in the last wall built. This is the west wall of the north wing, at the end of the arcade which extends from the transept. Temporarily set in plaster in 1928 with the thought of westward extension of the arcade to form a quadrangle, it was finished in stone after the Second World War.

Viewed on a sunlit afternoon, this wall displays the variety of texture and color provided out of the earth. It also suggests the care taken by the builders to find stone that would be worthy of its destined place. Here are found luminous pink and buff stones, often striated, from the Schawangunk Range east of the Catskills; other New York stone, the cooler, black-streaked pieces from near West Point; a few stones from near Zionsville, Pennsylvania, marked with large jet spots of feldspar. In other places around the Cathedral we shall find other stone from afar—granite from Plymouth, Massachusetts, as seen in the Ezekiel Tower to the south, and from Westerly, Rhode Island; Mohegan granite from Peekskill, New York, standing in fine-grained strength in the interior tower piers at the crossing and in some of the exterior steps; warmly patterned sandstone from near Cleveland, Ohio, for the interior walls and columns; and Kentucky limestone, whitening with the years, in pinnacles and cornices, weatherings and window tracery. We shall observe some of these more closely; but first, in the wall before us, one more type of stone stands out in the peculiar beauty of its tones.

This stone is a warm gray, at times iridescent, mixed with deep pink and striated with a soft green, as if lichen had become part of the rock through ages. A builder would go far to find stone with grain and variegation like this. Yet this stone was quarried out of a hillside above the Pennypack Creek less than a mile down the valley from the Cathedral site. The quarry was opened for the church's building, and closed before the edifice was completed. From it came the entire exterior masonry of the main structure, and much of the cut stone, as well as many pieces for the later additions to south and north, as in the wall at which we have looked.

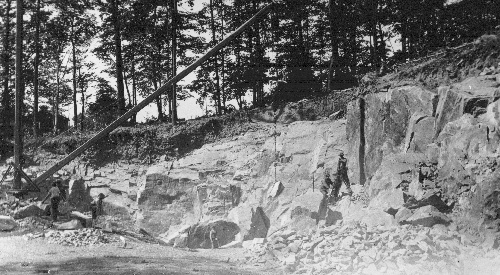

The quarry at Bryn Athyn, from which all the stone for the exterior walls of the church building was taken. Its opening followed intensive search for suitable stone throughout the northeastern United States. Click on image for a larger version.

Such a signal stroke of good fortune, like that called a miracle by Abbot Suger at St. Denis in the twelfth century, was not mere accident. The architects and builders had spent the spring of 1913 scouring nearby cities for examples in use of fine stone from which to erect the Cathedral; but as a youth Raymond Pitcairn had also roamed the countryside around the newly settled community of Bryn Athyn. His own recollection of the discovery and opening of the Bryn Athyn Quarry is worth quoting for the event it records and the sphere it evokes:

Until need of stone for the Church arose, the site of this quarry was marked by a square and massive boulder which overlooked Bryn Athyn's wooded picnic grounds. As girls and boys we had learned to know this woodland and the creek below; we loved the beauty of the sunlight filtering through green leaves that cast their shadows on the trunks of beech trees; we loved the camp fires and corn roasts, the shouting and the songs, and by the water's edge the landing where the girls stepped daintily into our light canoes, that slid so silently beneath branches of hornbeam and the loftier trees that overhang the stream.1

An echo, this, of more quietly-paced days in the lovely valley on which the Cathedral still looks down. But to the event:

It was on a hot midsummer afternoon that Alexander Moir, the superintendent of my father's estate, came carrying a small stone hammer to go with me to the woods, above the picnic grounds, to see an outcropping of boulders which he believed were just what I desired for the building of the church. And it was Mr. Moir who, with a few Italians in my father's employ, made the preliminary opening of the quarry and took out sufficient stone to build the first sample wall . . .2

And so the road that leads down to the Pennypack below the church is the Quarry Road today. Up its winding length toiled teams of horses with ton after ton of rough-hewn stone—metamorphic granite, or gneiss—to be worked and placed, each stone with individual care, by the men gathering in increasing numbers to build the church. By July 15, 1914, Edwin Asplundh reported to Pitcairn that there were seventy-four masons on the job, with more coming.

The month before, on June 19,3 1914, the cornerstone of the Cathedral had been laid with fitting ceremonies. It too is Bryn Athyn granite, taken from the slope above the Quarry Road just before it emerges from the woods, where the stone had lain for centuries a rain-washed boulder above the ground. Uncut by the hand of man, it fills the southeast corner of the sanctuary, a foundation for wall and buttresses. On it are the Hebrew characters signifying "the Head of the Corner," carved the day before the ceremony by Edward Kessel, who had been placed in charge of the quarry and was one of those whose work at the Cathedral led him to the faith of the New Church.

Noting the beauty of the Bryn Athyn stone, Pitcairn also wanted to use it for mouldings, capitals, bases, and other cut stone purposes. The architect in Boston foresaw difficulties because of the stone's hardness and grain; but Pitcairn, viewing these qualities as strengths rather than limitations, went ahead. The rightness of his prevision and the skill of the stone cutters are given testimony by the use of the local stone in the south porch, the north transept stair turret, and especially in the central tower.

This shows something of the detail of design in the tower stair where it runs straight for a little while near the organ loft. The underside of this flight may be seen from behind the organist's seat. Click on image for a larger version.

Looking down on the ribbing of the sanctuary vault above the altar. On the underside of the four drums were later carved the heads of the four beasts described in the Book of Revelation. Click on image for a larger version.

Also remarkable in design and execution is the intricate stone cutting in many parts of the church's interior. Two examples may be noted. The first is the stair hallway near the chapel sanctuary, of which several stones include a complete step and part of a molded arch. The other is in the joining of the arches at the head of the south chancel aisle where it opens to the chancel, the curved lines of the two arches interlacing to their base. Nor do these represent merely intellectual problems of stereotomy; the concern they exemplify was care for strength and beauty in the structure, and in the mind's response. And this in harmony with the principle that to build worthily, beautiful materials must be selected out of nature's Divinely ordained abundance, and allowed to express their beauty naturally by the manner of their fashioning.

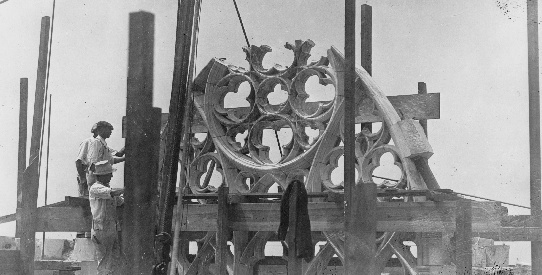

Growing upward toward completion like the opening of a living flower, this delicate tracery will crown the west window, and meanwhile stands supported against the bleak sky. Click on image for a larger version.

Three courses of sandstone form the start of two arches springing from the same column, to be set at the end of the chancel arcade. The interlacing curves carry the organic beauty of nature into formal art. Click on image for a larger version.

In 1914 another major decision was made, that the interior walls of the Cathedral should not be plastered, as originally specified, but should instead be lined with stone. For this purpose, an Ohio sand stone was selected from a quarry near Cleveland, after several trips to the area by the builders. Called by those who quarried it Variegated Amherst Buff, its tones are warm and rich, with an interesting and varied grain. It is seen at its best in the hand-cut window jambs of the nave aisles and the slender columns which support the clerestory. Its beauty in the ashlar-coursed walls is not quite of equal character, due to the fact that it was machine-planed at the quarry and given only a hand-tooled finish at the site. This is the only instance in the church of stone not worked down by hand.

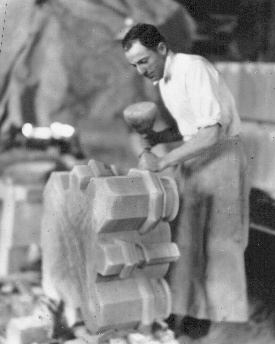

Working with mallet and chisel in the stone shed, on the sandstone base of a nave column. Click on image for a larger version.

A further illustration of far-sighted care in the selection of materials is the stone used for the exterior trim of the main building. Limestone was the traditional and natural choice; but the builders had seen too many examples of limestone buildings grown dark with time to be sanguine about coupling this stone with the light, warm Bryn Athyn granite. After consultation with experts and visits to quarries in the midwest, a time-tested oolitic limestone was chosen from Bowling Green, Kentucky. This finely grained stone contains a natural oil which bleaches as it weathers; and its growing whiteness through the years is a striking element in the Cathedral's beauty, whether viewed in the sunlight falling on a balustrade, outlined in string course and coping when the Cathedral is lit on a clear June night, or when the pinnacles stand out against the dark mass of a thunderhead.

|

Click on image for a larger version. |

Click on image for a larger version. |

Click on image for a larger version. |

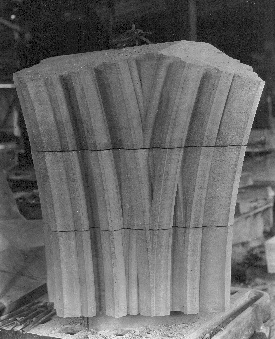

One of the lessons of the complex architecture, known by the Gothic builders, and unlearned in other eras, is that the part serves the whole and is thereby glorified. This limestone pinnacle, stunted and stolid upon the ground, will reach exultant from its base high in the air. Click on image for a larger version.

Inside, the floor of the nave and chancel is paved chiefly with seam-face granite quarried in Plymouth, Massachusetts. With surfaces made even by nature, its strong browns and grays are laid in an interesting variety of patterns; one of the most striking is to be seen in the outer chancel, three steps up from the nave. Throughout the Cathedral these larger stones are set among clusters of small quartz and flint like pieces, many of which were gathered for use in the church from the fields of the nearby Academy farm by the Bryn Athyn school children.

These, then, are the stones used for the central building of the Cathedral: Bryn Athyn granite for the exterior walls and much of the cut stone; Ohio sandstone for interior walls and trim; Mohegan granite from New York in the great piers and steps; Kentucky limestone for exterior trim; and Plymouth granite in the floors.

Raymond Pitcairn inspects the stairway under construction between the vestry and chapel, near the south transept. This stairway contains some remarkably complex planes shaped from a single stone, as is suggested by the one resting atop the railing and comprising parts of wall, tread, and riser. Click on image for a larger version.

Of the principal organizations of masons and stone cutters, clustered about the rising walls or working on rough blocks in the long reaches of the dusty stone shed, the previous chapter took note. A brief word must be said of the carvers who wrought pinnacle and tracery, leaf and flower and symbolic figure out of these stones.

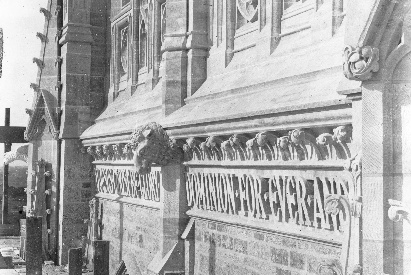

This view of the main tower, taken before the scaffolding was removed, gives dramatic point to the magnificent carving which accompanies the inscription beneath the cornice. These heads were carved in place from blocks of stone set rough-hewn. The eagles at each corner represent the Divine Providence guarding over the life of the church, and also human vigilance and insight in preserving doctrine. The four heads centered on the facades are the beasts of the Apocalypse who worshipped at the throne of the Lamb. Click on image for a larger version.

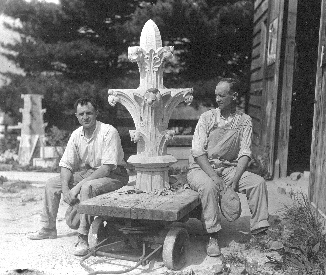

Names like Menghi and Marchiori out of southern Europe, Tweedale from the Scottish north, brought with them a tradition reaching back into the Middle Ages. No mere executors of another's designs, they took pride in contributing individual talents to the carving. Robust and open-hearted, they delighted in a spirit of joyous competition, the true rivalry of companionship. One memory will serve as instance: of Attilio Marchiori, a strong, brown-bodied Italian, high on the tower scaffolding, carving on one of the eagles at the corners, with each foot in a bucket of water to keep cool, and singing while his fellows below laughed to watch and hear.

The work is done now, the ring of the hammer on chisel and the slow swinging of stones into place. But that which remains speaks eloquently of what was done here, and these stones will stand for coming generations.

Top | Previous Chapter: Shops and Artisans | Next Chapter: The Timber Work | Table of Contents

Footnotes top

1 Raymond Pitcairn, "Bryn Athyn Church: The Manner of the Building and a Defence Thereof" (book draft, Glencairn Museum Archives), 17 (draft two).

2 Raymond Pitcairn, "Bryn Athyn Church: The Manner of the Building and a Defence Thereof" (book draft, Glencairn Museum Archives), 17 (draft two).

3 A significant date in the history of the New Church. On June 19, 1770, Swedenborg records that the Lord called together His disciples who had followed Him in the world, and sent them throughout the spiritual world to proclaim that "the Lord God Jesus Christ reigns, whose kingdom shall be for ages of ages." This spiritual event, which also marked the finishing of Swedenborg's climactic work of revelation, The True Christian Religion, is celebrated as the Church's distinctive holiday.