Bryn Athyn Cathedral: The Building of a Church

E. Bruce Glenn

A Church of the New Christianity

THE CATHEDRAL is dedicated to the worship of God in a new vision of His Divine Humanity. The "New Church," of which the General Church of the New Jerusalem is an organized body, is not to be regarded as a sect of Protestant Christianity. Founded on the theological writings of Emanuel Swedenborg in the eighteenth century, it is a New Christian Church, distinct from all the branches of the faith founded after the Advent. While on earth, the Lord had given a new commandment to his disciples, a vision of deeper truths that had lain hidden within the Mosaic scripture to the Israelites, and had thus established a new dispensation of His love and wisdom by means of the Gospels. And now, as He had chosen Moses, the prophets, and the evangelists to set down His Word in successively deeper penetrations of the human mind and heart, He gave a new revelation of truth through Swedenborg—a revelation to the developing rational mind of the race that shows an inner sense within the letter of the Old and New Testaments, one that tells plainly of the Father, as He had promised the disciples. He said that He would come again as the Spirit of Truth; and in the apocalyptic vision of John on Patmos, He gave the symbolic prophecy of the New Jerusalem descending out of heaven—a new heaven and a new church on earth, freed from the falsities of human misinterpretation.

Indeed, the whole of the Book of Revelation is a prophecy of His second coming, now fulfilled in the doctrines given through Swedenborg as the further opening of the Holy Scriptures. In these doctrines is set forth the unity of the one God as Divinely Human; the laws of His merciful Providence; the nature and order of the heavens for which He creates every man as an individual form of active use, and of the hells toward which man's inherited tendencies will lead if, in freedom, he does not shun evils as sins against God; the nature of the human mind which is the man himself, and whose immortal and eternal destiny is formed by the loves he cherishes in his following or rejection of the Lord's Word. "The spirit quickeneth"; and from the late eighteenth century, there have been those who, finding Swedenborg's more than thirty theological volumes, had their hearts quickened by the truth they saw in this infilling of the letter of earlier Scriptures.

A devoted group of families had settled in Bryn Athyn in 1897 to establish a distinctive life and educational system founded on the new doctrines. This small but growing congregation had worshipped successively in an old stone barn, a wooden frame school-and-clubhouse, and in the chapel of the Academy's central building erected in 1904. Meanwhile a church building fund had been started among the residents; and in 1908, John Pitcairn, founder of the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company, made a substantial gift for the building of a house of worship apart from other community functions. John Pitcairn's Scottish business acumen was matched by a vital interest in ecclesiastical and civic uses; together with New Church friends in Philadelphia, he had seen the vision of a religious community, had purchased the land for its establishment, and had endowed its educational center.

A longtime friend and associate, the spiritual leader of the movement at that time, was Bishop William Frederic Pendleton. For several years he had been making an intensive study of ritual for the church leading to the compilation of a liturgy. Now he was presented with the question as to what type of church building would be best fitted for the forms of worship he and others had drawn from the doctrines of the church. He concluded that the Gothic plan best answered to these needs.

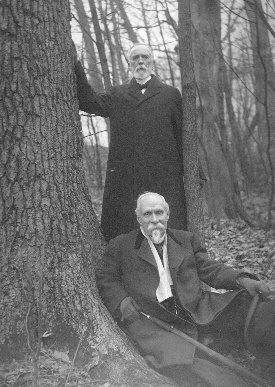

These distinguished leaders of the church at the Cathedral's inception are beside one of the great white oaks felled near Bryn Athyn for the roof trusses. Standing is Bishop William Frederic Pendleton, first executive of the General Church and developer of the ritual embodied in the form of the church. Seated before him is John Pitcairn, Scottish immigrant and industrialist, whose generous gifts were instrumental in the founding of Bryn Athyn and the Academy, and permitted the unique methods by which the Cathedral was built. Click on image for a larger version.

Why, it may be asked, go back seven hundred years to an older faith to find an architectural embodiment for the new? A natural question, and one that gave the builders pause in their planning.

The answer, in one sense, is the Cathedral itself. Surely the fidelity of these lines rising from the earth, the steadfastness of buttressed walls joined with the upward yearning of arch and pinnacle, are the expression of a living belief and not simply antiquarian nostalgia. In support of this eloquent justification, sensitive critics have long held that the church architecture of the Middle Ages is unsurpassed in its uniting of religious faith, artistic beauty, and social harmony. John Ruskin's The Stones of Venice, Emile Male's Religious Art in France of the XIII Century, Henry Adams' Mont-St-Michel and Chartres—Englishman, Frenchman, and American, each in his way attests to the power and splendor of the medieval cathedral, the devoted faith of those who erected it.

Yet Ruskin, Adams, and Male were historians of a past culture; and the first two decried the half-hearted attempts of nineteenth century builders to return to that culture, seeing therein but an empty gesture toward an irrecoverable past. For between the two eras had come shouldering the secular renaissance and the industrial revolution, bringing with them a whole reordering of social, artistic, and economic values. The anonymous religious craftsman of the Middle Ages had given way to the artist who signed his work under the patronage of duke or merchant; and the medieval flèche, the stones of which were cut on the site and lifted with a care that knew no hurry, was but poorly and heavily imitated by its Victorian counterpart raised by contract to specifications carried out in the mill. The twentieth century creates instead a spire of stainless steel, the glistening surface of which declares the skills of a machine age.

The Bryn Athyn Cathedral is a different kind of triumph for the human spirit—a revivification, upon the foundation of a new truth, of the forms and methods of the great Christian tradition. As one noted scholar and critic expressed it after visiting the yet uncompleted church in 1917:

I had expected much of the Bryn Athyn church, but nothing like what I found. If it existed in Europe, in France or England, it would still be at once six centuries behind, and a hundred years ahead of its time. But on the soil of great architectural traditions, it would be in a measure comprehensible, and the presence in the neighbourhood of the great works of the past would in a way prepare the mind for this achievement of the present age. For your church, alone of modern buildings, in my judgment, is worthy of comparison with the best the Middle Ages produced.1

Thus wrote Kingsley Porter2 in a letter to Raymond Pitcairn, John Pitcairn's eldest son, who was directly engaged in the church's design after its first inception, and who entirely directed the building as it grew into its completed form. Of Pitcairn's development of a building method unique on its scale in modern economy, the following chapters will treat. Regarding the choice of early Gothic architecture for the Cathedral, he wrote in 1920, after the dedication of the main building:

In the last days of an epoch, an autumnal renaissance transpires; art flourishes, and through art the spirit of a passing age is clothed in ultimate and lasting forms. . . . Christian symbolism and the traditions of primitive Christian faith have been preserved in like manner in the great cathedrals of the Middle Ages. . . . The New Church has in them a heritage of Christian art vast and beautiful. . . . Moreover, it must be true of the Lord's new coming, as of His first advent, that He "came not to destroy, but to fulfill" the teachings of the former Revelation, whose worship was solemnized in these cathedrals, whose art portrays in many beautiful and graphic forms the story of the Christian gospel. . . .3

A new Christianity, whose revelation of an inner meaning gives new light and power to the Old and New Testaments, may also find in the ennobled art of that older day a true vessel in which to express its worship.

Our century has heard much about organic architecture, the word popularly connoting functionalism or a natural relation to the environment. More broadly, organic means having living qualities—growth, complexity, capability of change, and this because the organic can be infilled with life from the Source of all life. For man is environed spiritually as well as naturally, and the works of his brain and hand ought to be functional in answer to more than physical needs. The churches of medieval Christianity were organic in this deeper sense. They grew from the faith of the people who built and worshipped in them, and they breathed that faith in ascending arch and vault, in the changing colors of storied glass and the carved figures on capital and corbel. It is this organic expression that carries the ring of sincerity even to the modern skeptic who knows them only as art. It is this organic functionalism, relating to life and belief, that enabled the builders of the Bryn Athyn Cathedral to use an old form while adapting it to a new belief.

Edwin Asplundh and Raymond Pitcairn count the rings on the stump of the oldest oak felled for the roof. This tree was 347 years old on that day in 1916. Asplundh organized and supervised the building forces on the site until his departure for the war in 1917; Pitcairn's was the guiding spirit in the design and erection of the Cathedral for nearly twenty years of an already active business and civic career. Click on image for a larger version.

Let us see something of the distinct features of the Cathedral which set it apart from the traditional Gothic it honors.

As noted earlier, the basic plan of the central building is the traditional Gothic cruciform. This was not followed because the New Church worships at the foot of the cross; indeed, the visitor soon notes the absence of the cross as symbol in the Bryn Athyn Cathedral. The risen Lord is the God of heaven and earth, the eternally Human Creator and Redeemer of men; and the nave and chancel, crossed by the transepts, are a figure of His Divine Humanity in whose image and likeness we are made. One of the central doctrines of the New Church—that of the "Maximus Homo" or Grand Man—teaches that the whole of the heavens are in a continually perfecting image of the human form, its interrelated organs and uses. Terrestrial creation also reiterates the human form as image of its Creator who alone is truly Man. This is a concept not merely of physical figure, but of the form and function within. All history and art testifies to the validity of the human impress upon the world and the inter-relation of all things. Thus the power of symbols lies in their human meaning in all its richness and variety. A single form contains manifold potentials of meaning, depending on the experience brought by the beholder, and the strength and depth of his inward ideal to which the external form corresponds.

Many aspects of the Cathedral are thus representative of human forms and meanings. Step through the west door and look up the central aisle. Ahead, set like a precious gem in soft lavender light, rests the focus of attention within this church—the Word as the mind of God given for man's understanding. Not the pulpit, for that is the place of man's exposition of the Lord's Word, the outermost point between chancel and nave, priest and congregation; not the sacramental altars for baptism and the Lord's Supper, though these stand closer as representatives of entrance to the "Holy of Holies." Beyond them is the Sanctuary, toward which all the planes of nave and chancel converge. There stands the altar of the Lord and upon it His Word in which is no letter written save by His Divine mind and set down at His command. Perhaps the most solemn moment of the Church's ritual is the opening of the Word upon this altar amid silence at the beginning of each service, representative of the opening of the inner sense of the Old and New Testaments in the Heavenly Doctrines given through Swedenborg. To quote a writer of the Church:

By this inmost recess of the chancel, where the . . . Word is placed, is represented the Lord's presence in the light of the open Word in the inmost of the New Church—a new light of Doctrine imparting new understanding and fruit in the administration of the sacraments upon the middle plane of the chancel, and orally taught by lesson and sermon from the lectern and pulpit on the outmost plane.4

This setting of the sanctuary in which the Word is held up before the eye and mind is a distinctive aspect of a new Christian architecture.

That not only the persons and events of Scripture, but the least details of their recounting have an inner significance, is set forth abundantly and systematically in the doctrines of the New Church. Thus, as was glimpsed by the medieval scholars and reported by Emile Male, numbers recur in significant patterns—three, twelve, forty.5 It is revealed through Swedenborg that twelve signifies completeness, fulfillment. Hence, one of the stipulations in the design of the chancel at Bryn Athyn was that it be divided into its three planes by twelve steps. This was done by separating the entire chancel from the nave by three steps, the inner chancel with its altars for baptism and the Holy Supper by three steps, and the sanctuary from the inner chancel by three steps, with the altar for the Word elevated by three steps in the center.

Viewing the church as a whole, another threefold division may be seen: that of sanctuary, chancel, and nave. These represent three planes of man's life: the human soul, man's inmost reception of life from God; his mind, the immortal individual which he becomes in his response to life; and the body which is his temporary abode on the earth. The same division into three parts symbolizes the three successive revelations of the Word to man, as may be seen in the symbolic carving and especially in the clerestory windows of stained glass which will later engage our attention. Briefly, the windows of the nave depict incidents in which the Angel of the Lord appeared to men of the Old Testament; the six chancel windows tell of episodes in the Lord's life on earth, centered around His six visits to Jerusalem; and the great cast window presents the Lord Himself, with the twelve apostles beneath to whom, Swedenborg recounts, the Lord gave the mission of proclaiming His new Word throughout the spiritual world while Swedenborg was setting it down for men on earth. To one who has not examined the Writings of the New Church in their full scope, this last statement may sound fantastic; but so, to many, did the Lord's teachings to those same apostles while on earth, and the miracle of His resurrection. And the Bryn Athyn Cathedral, like those of medieval Christianity, was not built to please the scoffer.

Turn now to view the great west window above the narthex. If it is afternoon, the window's five lights are ablaze from the westering sun. The subject of the window is one of the most striking examples of symbolism drawn from the doctrines of the Church and using representative figures from the Old and New Testaments. These doctrines teach that since the dawn of the race, five churches have existed successively in which the true God has been worshipped through His Word. The names given them in Swedenborg's works are the Most Ancient, the Ancient, the Israelitish, the First Christian, and the New Christian Church. Each is represented by one light of the west window. Adam, on the left, is representative of the Most Ancient Church. His story, told in the first chapters of Genesis, is not that of an historical individual but an allegory of the first church before the Fall. Beside him, Noah stands as representative of the Ancient Church drawn from the remnant of those who worshipped the Lord despite the flood of false reasoning and evil that suffocated the first church. To the far right, Aaron symbolizes in his priestly office the giving of the Lord's Commandments to His chosen people, and His guiding of their destiny as the third, or Israelitish Church. Next to him is John the disciple and evangelist, he whom the Lord loved and who declared in his gospel the new doctrine of Divine love and mercy, the Word made flesh. And it was John, exiled on the Isle of Patmos, who wrote down the apocalyptic vision resplendent in the central light of this window: the woman clothed with the sun who represented the New Christian Church to come on earth, who dwelt in the wilderness until the truth which she bore as Manchild might grow to maturity.

It will be noted that none of the windows in the central church building present figures apart from the Word. In the same vein, a definite departure from the tradition of the medieval churches is the absence of carved figures depicting saints' legends and personages in ecclesiastical history. Artistically, this absence lends a greater simplicity to the structure, a simplicity reinforced by the underlying reason. The Bryn Athyn Cathedral is a house of God, not of men. On the authority of His Word rests the continuing purity of His Church, and not upon the imagination or reasoning of men. The humanistic Renaissance, with all that it contributed to the freeing of the mind in preparation for the New Christian Church, nevertheless brought about the secularization of Western culture. From that time to this, nothing has been created to proclaim the spiritual hopes and aspirations of men that equals the great churches which went before. If in the following pages the story of the Bryn Athyn Cathedral suggests a new aspiration, as the Cathedral itself embodies a renewal of high artistic motives, it is because it stands upon a new and deeper affirmation of the truth that moved men's minds and hearts seven hundred years ago.

Top | Previous Chapter: First Vistas | Next Chapter: Organic Design | Table of Contents

Footnotes top

1 A. Kingsley Porter. Letter to Raymond Pitcairn. 24 October 1917. Glencairn Museum Archives, Bryn Athyn, PA.

2 Porter, Professor of Fine Arts at Yale University, served with a commission to restore French cathedrals damaged in the First World War, and visited Bryn Athyn on several occasions.

3 Raymond Pitcairn, "Christian Art and Architecture for the New Church," New Church Life 40 (October 1920): 614–615.

4 Editorial Department, "The Bryn Athyn Cathedral," New Church Life 38 (November 1918): 688.

5 See Emile Male, Religious Art in France, XIII Century: A Study in Mediaeval Iconography and Its Sources of Inspiration (London: J.M. Dent, 1913), 5–14.