"A Necessary Spring of Popular Government": The Importance of Religion and Public Morality for the Early American Republic

Brian

D. Henderson

Faith and Learning

at Bryn Athyn College of the New Church. Ed. Dan A. Synnestvedt.

Bryn Athyn,

Pennsylvania: The Academy of the New Church, 2004. 99–119.

History can serve as a mirror to cast a reflection of our present time and culture to see where we once were—to use our past as a way of putting our present into perspective and looking at its roots. As historian John F. Wilson wrote, "The present is reflected in concern with a past that gives it legitimacy, and the past is clarified in the present, which is perceived to flow from that past."1 The New Church historian possesses an additional tool with which to utilize this mirror. In looking at the past, we can not only look at the political, social, economic, or religious history of a people, but get glimpses into their spiritual history by asking questions such as: what did a people value both naturally and spiritually? What values did their society rest upon and what gave rise to those values? In searching for answers to questions such as these we can begin to see that history in many ways is the story of how mankind has received and reacted to the Lord's influx.

A popular columnist recently suggested by that in our culture today "religion is akin to secondhand smoke—something that thoroughly enlightened modern people find obnoxious, and from which the public must be protected."2 Many scholars have traditionally held that religion forms the origin and basis of culture. If in our present culture the public must be protected from religion, what is the basis of our culture today? What is it that we value? Does our culture in general value anything spiritual? Most importantly, what are the ramifications regarding the impact of these answers on the state of our culture? In examining the current place of religion in our culture we should make use of the mirror of history to see reflected in it our founders'' views concerning religion's place in society and culture.

Within the discipline of history the field of religious history has grown tremendously over the past decade. Increasingly historians are beginning to examine just how important a role religion played in the decisions and events of our past, the role religion played in the shaping of our nation and our culture. Finally, historians are exploring questions regarding the role religion played, for example, in the founding of the American republic. Just how important was religion to the culture of the early republic? Was religion in fact the origin and basis of American culture? If in fact religion did play an integral role in the formation and very survival of the American republic, if it lay at the very core of early republican culture, how can we begin to apply this reality of our past to our present condition? Can we in fact discover a past which gives our present culture legitimacy?

Part of what influenced my choosing the topic for this talk stems back to a colloquium given by Reverend Walter Orthwein this past fall on applying spiritual principles to civil order.3 In his talk he eluded to the fact that although there is a great deal of debate today concerning the separation of church and state, what we really see in our society is an increasing separation of religion from the state. I am confident that each of you could call on a myriad of examples of cases in which religion is being removed from our society, cases in which the Constitution is evoked in bringing about this separation: courts have ruled that nativity scenes, to be constitutional, must include a quantity of secular symbols; residents of a San Francisco public housing complex are allowed to use their community room to host outside speakers, including from the nation of Islam, but they cannot use it for Bible study, on the principle that the separation of church and state precludes using "federally funded units to promote interests in the church." In Arizona, the ACLU recently persuaded a court to issue a restraining order to prevent the mayor of one town from declaring a "Bible week." In Medford, New Jersey, when a 6 year-old boy chose a portion of the story of Jacob and Esau from Genesis to read to his first grade class, he was forbidden to read it. In Cincinnati a law suit is challenging the law which recognizes Christmas as a federal holiday.4

Religion is slowly being driven from our culture. Is this what the framers of the Constitution envisioned in calling for a separation of Church and State? How far have we come from the original intent of the founding fathers when the First Amendment is used to stamp out the expression of religion? Is this what they intended? Did our founding fathers believe that the public had to be protected from religion?

One must consider how the founding fathers viewed religion and its role in their society. For if we are to look to the past to give our present legitimacy, we must be careful not to fall into the trap of presentism—we must be mindful to put the past into its proper context and not view the past according to our present-day values.

The founders spent a great deal of time discussing the importance of public virtue and the common good to the very survival of the young republic. The question at hand is where they saw that virtue stemming from and what they meant by the common good. Did religion in their minds play a vital role in establishing this public virtue and common good and thus in turn rest at the core of the culture of the new republic?

It is first necessary to comprehend how the founders understood liberty. For them, liberty embodied a meaning far deeper than just that of the personal, individual liberty we hold so dear in society today. True liberty was "natural liberty restrained in such manner, as to render society one great happy family; where everyone must consult his neighbor's happiness, as well as his own."5 According to classical republican tradition, man was by nature a political being, a citizen who achieved his greatest moral fulfillment by participating in a self-governing republic. Thus, according to the "harmonizing sentiments of the day" the most important liberty was not personal liberty, but rather public liberty. It was this public liberty which defined personal liberty and provided the means by which the personal liberty and private rights of the citizen were protected.

"A Citizen," wrote Sam Adams, "owes everything to the Commonwealth." Added Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia, "Every man in a republic is public property. His time and talents—his youth—his manhood—his old age—nay more, life, all belong to his country." "No man is a true republican," wrote another Pennsylvanian in 1776, "that will not give up his single voice to that of the public."6 Individual liberties could be reconciled with the greater common good for the simple reason that the most important liberty was seen not to be personal, but rather public, or political liberty. The private liberties of individuals depended upon their collective public liberty for survival.

In the minds of the founders, for a republic to be successful each man had to subjugate his personal wants to the greater good of the whole. The willingness of the individual to sacrifice his private interests for the good of his community, this the founding fathers meant by public virtue.

Liberty, then, was realized when the citizens were virtuous—that is, willing to sacrifice their private desires and interests for the public interest and for the sake of the community, or the common good. A comparison between the founders' views concerning this and what Swedenborg penned concerning the common, or public, good is interesting. We read in Spiritual Experiences,

He who is in genuine love has an idea of the common good and of the universal human race, in respect to which every individual man should be as nothing, as is known; wherefore unless a man regards himself as associated with his fellow, and esteems himself as nothing in respect to the common good, and love his neighbor better than himself, he can by no means be in the unanimous body (heaven), but he necessarily expels himself from it, so much as he removes himself from that love.7

The Writings state very clearly that this idea of the common good and this love of the neighbor come from the love of use which in turn comes directly from the Lord. As the Apocalypse Explaind teaches

The essence of uses is the public good. With the angels the public good in the most general sense means the good of the entire heaven, in a less general sense the good of the society, and in a particular sense the good of the fellow citizen. But with men the essence of uses in the most general sense is both the spiritual and the civil good of the whole human race, in a less general sense the good of the country, in a particular sense the good of a society, and in an individual sense the good of the fellow citizen; and as these goods constitute the essence of uses, love is their life, since all good is of love and the life is in the love.

. . . This is because no one can be kept by the Lord in love to the neighbor unless he is in some love for the public good; and no one can be in that love unless he is in the love of use for the sake of use, or in the love of use from use, thus from the Lord. [emphasis added]8

The founders believed that the virtue needed to support the public good stemmed from the moral character of its people, which in turn, in the minds of many in the early republic, came from religion.

If the entire survival of the republic, in the minds of our founding fathers and their society, depended on public virtue, based in public morality, which in turn for many was nurtured by religion, the question could be asked what role the government should play in fostering that morality. To what extent was the government responsible for nurturing the public morality so necessary for its own survival? Did the government attempt to shape a moral culture in the new nation?

The answer to this question seems to be that the Confederation Congress took strides in this direction which might surprise some. The Confederation Congress, under the Articles of Confederation, served as the governing legislative body of the United States from 1774 to 1789, from the American Revolution until it was supplanted by the Constitution of the United States. Although the Articles of Confederation did not officially authorize the Confederation Congress to concern itself with religion, many historians have begun to argue that this Congress invested more energy encouraging the practice of religion in the new nation than any subsequent American national government—it appointed chaplains for itself and the armed forces, sponsored the publication of a Bible, imposed Christian morality on the armed forces, and granted public lands to promote Christianity among the Indians. At least twice a year during the American Revolution Congress proclaimed national days of thanksgiving and of "humiliation, fasting, and prayer."

At its initial meeting in September 1774 the Confederation Congress invited the rector of Christ's Church in Philadelphia to open its session with a prayer. From this point on the Confederation Congress, and after it the Congress under the Constitution, appointed chaplains. The Confederation Congress set aside November 28, 1782 as a day of thanksgiving on which Americans were "to testify their gratitude to God for his goodness, by a cheerful obedience to his laws, and by promoting, each in his station, and by his influence, the practice of true and undefiled religion, which is the great foundation of public prosperity and national happiness."9

Congress devoted three of the first four articles in the opening section of the regulations governing the conduct of the Continental Army to the religious nurturing of the troops. Article 2 "earnestly recommended to all officers and soldiers to attend divine services."10 Regulations for the navy prescribed punishments for swearers and blasphemers: officers were to be fined and common sailors were to be forced "to wear a wooden collar or some other shameful badge of distinction."11

When war with Britain cut off the supply of Bibles to the United States, the Confederation Congress instructed its Committee of Commerce to import 20,000 Bibles. When Philadelphia printer Robert Aitken petitioned Congress to officially sanction a publication of the Old and New Testament a Congressional Resolution stated that Congress "highly approve the pious and laudable undertaking of Mr. Aitken, as subservient to the interest of religion . . . in this country, and . . . they recommend this edition of the bible to the inhabitants of the United States."12

In passing the Northwest Ordinance in 1787 Congress declared religion and morality to be indispensable to good government, writing in Article 3, "Religion, Morality and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, Schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged."13

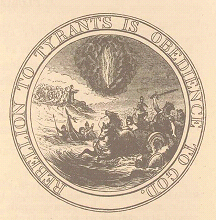

When

the Confederation Congress appointed Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and

John Adams to create a seal for the infant nation Franklin proposed an adaptation

of the Biblical story of the parting of the Red Sea while Jefferson recommended

the Children of Israel in the Wilderness, led by a pillar of cloud by day and

a pillar of fire by night.

When

the Confederation Congress appointed Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and

John Adams to create a seal for the infant nation Franklin proposed an adaptation

of the Biblical story of the parting of the Red Sea while Jefferson recommended

the Children of Israel in the Wilderness, led by a pillar of cloud by day and

a pillar of fire by night.

Eventually Jefferson embraced Franklin's proposal, rewrote it, and proposed the seal to Congress. Although not accepted, these drafts reveal something of the religious climate of the period when one considers that Franklin and Jefferson, two of the most theologically liberal of the Founders, chose Biblical imagery for this important task.

It can be argued then that this first national government of the United States was convinced that the public welfare of American society depended on the vitality of its religion. The Confederation Congress itself declared to the American people that nothing less than a "spirit of universal reformation among all ranks and degrees of our citizens," would "make us holy, that we may be a happy people."

During the Constitutional Convention, when the Convention seemed on the verge of breaking up over its failure to resolve the dispute between the large and small states over representation in the new government, Franklin asked that each day's session begin with prayers. Although his motion failed, it is interesting to note Franklin's words: "the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this Truth—that God governs in the Affairs of Men. I also believe without his concurring Aid, we shall succeed in this political building no better than the Builders of Babel."14

Even after the Confederation Congress yielded to a new government under the Constitution, the country's first two presidents, George Washington and John Adams, were believers in the importance of religion for republican government. As citizens of Virginia and Massachusetts both had been sympathetic to general religious taxes being paid by the citizens of their respective states to the churches of their choice. It is true, however, that both would have discouraged such a measure on the national level because of its divisiveness. They confined themselves to promoting religion rhetorically, offering frequent testimonials to its importance in building the moral character of the American citizens, that, they believed, lay at the very heart of public order and successful popular government.

In what has become known as his Prayer for America, Washington asked God to "dispose us all, to do Justice, to love mercy, and to demean ourselves with that Charity, humility and pacific temper of mind, which were the Characteristics of the Divine Author of our blessed Religion, and without an humble imitation of whose example in these things, we can never hope to be a happy Nation."15

Many consider George Washington's Farewell Address to be one of the most important documents in American history. While Washington's recommendations concerning foreign affairs exerted strong and continuing influence on American statesmen and politicians, the "religious section" of the address was for many years as familiar to Americans as his warning to avoid entangling alliances with foreign nations. Washington's observations on the relationship of religion to government were commonplace. In his address, Washington advised his fellow citizens that "Religion and morality" were the "great Pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of Men and citizens." He added that "National morality" could not exist "in exclusion of religious principle." He concluded by adding, "Virtue or morality," as the products of religion, were "a necessary spring of popular government."16

For Washington religion was indispensable in maintaining the moral health of the nation. As he observed, a nation cannot survive without morality, and morality comes from religion. One of the principles for which Washington stood, therefore, was that religion and morality mutually and indispensably supported political prosperity and human happiness. A nation's laws spring from its morals and its morals spring from its religion. As Washington said, "It is impossible to govern rightly without God and the Bible." Washington's beliefs here seem to echo closely a portion of Divine Providence which reads,

Consider whether you can think analytically concerning any form of government, or any civil law, or moral virtue, or spiritual truth, unless the Divine out of His wisdom flows in through the spiritual world. For myself, I could not and can not.17

Alexander Hamilton, who drafted Washington's Farewell Address, made an even stronger case for the necessity of a divinely religious faith as a foundation for government than Washington. While Washington incorporated Hamilton's assertion that it was unreasonable to suppose that "national morality can not be maintained in exclusion of religious principle," he was not willing to go so far as to include Hamilton's next sentence, "does it [national morality] not require the aid of a generally received and divinely authoritative Religion?"18

The status of "generally received and divinely authoritative Religion" in terms of the relationship of that religion to the state had begun to be raised after independence as the states were required to write individual constitutions establishing how each would be governed.

In writing these state constitutions, clearly one of the most contentious issues was whether the state would support religion financially. The states were in a stronger position to act upon this issue because they were considered to possess "general" powers as opposed to the limited, specifically enumerated powers of Congress.

In Massachusetts the battle over state-supported religion was between the Congregationalists and the Baptists. The ministers of the Congregational Church, which had received public financial support throughout the colonial period, advocated a policy of "general assessment"—on the grounds that religion was necessary for public happiness, prosperity and order. The Baptists, who had grown both in strength and numbers since the Great Awakening, tenaciously adhered to their conviction that churches should receive no support from the state—the Divine Truth, they argued, having been freely received, should be freely given.

In the end, the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention chose to act as "nursing fathers" of the church, authorizing a general religious tax to be directed to the church of a tax payer's choice.19 "The happiness of a people," they wrote, "and the good order and preservation of civil government, essentially depend on piety, religion, and morality."20

In Virginia Patrick Henry sponsored a similar bill in 1784 which levied a tax for the support of religion but permitted individuals to earmark their taxes for the church of their choice. This bill was supported by future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, John Marshall. Opponents, led again by the Baptists' argument that government support of religion corrupted it, bought time to organize resistance, however, by electing Henry Governor.

Supporters of Henry's bill countered by declaring,

The Christian Religion is conducive to the happiness of society. True Religion is most friendly to social and political Happiness—That a conscientious Regard to the approbation of Almighty God lays the most effectual restrain on the vicious passions of Mankind affords the most powerful incentive to the faithful discharge of every social Duty and is consequently the most solid Basis of private and public Virtue is a truth which has in some measure been acknowledged at every Period of Time and in every Corner of the Globe.21

George Washington did not, in principle, oppose, "making people pay towards the support of that which they profess," although he considered it "impolitic" to pass a measure that would disturb public tranquility.22

Richard Henry Lee supported Henry's bill, believing the influence of religion to be the surest means of creating the virtuous citizens needed to make a republican government work. Lee wrote, "Refiners may weave as fine a web of reason as they please, but the experience of all times shows religion to be the guardian of morals."23 This remark appears to have been aimed at Thomas Jefferson who, at this point in his career, was thought by other Virginians to believe that sufficient republican morality could be instilled in the citizenry by instructing it solely in history and the classics. Reflecting the Enlightenment reliance on human reason, Jefferson's moral philosophy was founded in the evidence presented by human nature itself, readily available to any astute observer.

The true fountains of evidence [are] the head and heart of every rational and honest man. It is there nature has written her moral laws, and where every man may read them for himself.24

On the topic of religion in society Jefferson once wrote, "The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurous to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no God. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg."25

James Madison, the leading opponent of government-supported religion, marshaled sufficient legislative support to defeat Henry's bill. Madison argued both that state-supported religion violated the citizen's unalienable natural right of freedom of religion and that government's embrace of religion inevitably harmed it. It was Madison who helped pass Jefferson's famous Act for Establishing Religious Freedom that brought the debate in Virginia to a close by severing, once and for all, the links between Church and State.

While the Church and State were split asunder in Virginia, this did not necessarily represent the majority view of American states in the 1780s. Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire implemented laws which required all citizens to pay a religious tax, whereby each individual was given the option of designating his share to the church of his choice. Such laws were passed but not put into effect in Maryland and Georgia.

The question of the relationship between Church and State moved from a state to a national level with the Constitution. Aside from Article VI, which stated that "no religious test shall ever be required as Qualification" for feudal office holders, the Constitution said little of religion. In fact, when it was submitted to the American public many pious people complained that the document had slighted God, for it contained "no recognition of his mercies to us . . . or even of his existence."

For this reason many have called the Constitution an utterly secular document, lacking mention even of the deist "Great Governor of the world" given credit to in the Articles of Confederation. However, the fact that religion was not otherwise addressed in the Constitution does not necessarily determine it an "irreligious" document any more so than the Articles of Confederation.

Historically there have been two commonly held beliefs concerning what the founders meant in the Constitution regarding the separation of Church and State. In the separationist reading of the Constitution religious liberty is understood to be the absence of governmental constraint upon individuals in matters of religion. In this way the emphasis falls on religious liberty as entailing individual action and liberty is conceived of negatively as an absence of external constraint.

The accomodationist reading of the Constitution asserts that the First Amendment was clearly not intended to be anti-religious. Instead, it was drafted precisely to protect the various religious practices of the states. Many of the delegates believed that the power to legislate on religion, if it existed at all, lay within the domain of the state, not the national government. These historians therefore assert that the First Amendment defines religious liberty as a positive right, the exercise of which is to be encouraged by the government. They construe religion less in terms of individual action and give liberty a positive value as something more than the absence of restraint. Thus they are more concerned with the exercise of religion and are aware of its communal aspects. They believe the First Amendment excluded only direct establishment or preferential treatment for a particular religion. Indeed, they believe that government should facilitate the practice of religion by both individuals and collective groups as essential to the common good.

A newer, third interpretation has recently been offered: that the Constitution said little about religion because the delegates believed that it would be a tactical mistake to introduce such a politically controversial issue as religion into the Constitution. The one basic driving objective of the delegates was to construct a framework which was adequate in making the infant government viable. For the delegates, the issue of religion was potentially the most divisive issue facing them. The only "religious clause" in the document—the proscription of religious tests as qualifications for federal office in Article VI—was intended to defuse controversy by disarming potential critics who might claim religious discrimination in eligibility for public office.

While the founding fathers were not anti-religious, their overriding and commonly held objective of achieving an adequate federal government could only be frustrated if the issue of religion's relationship to the federal government were allowed to arise. Any federal power over religion would have gone against the established power of the states in the issue of religion and could have proved to prevent the ratification of the Constitution. Thus, the First Amendment religion clauses were designed to place explicit limitations upon Congress, assuring those who were skeptical of federal power that the existing state practices regarding religion would be protected from federal intervention. The one basic driving objective of the delegates was to frame a government which was adequate in making the infant government viable. The delegates, then, strategically avoided the issue of religion specifically because it was potentially the most divisive issue facing them.

The founding fathers proposed neither the wholesale segregation of religion from government, nor that the federal government should take over religion. Rather they held that religious institutions lay beyond the authority of the federal government. Such was appropriate, they believed, for a religiously plural society. Religious activities remained a crucial part of the social and cultural fabric of the new nation, but the distinctively limited federal government had no mandate to supervise them.26

Historian Gordon Wood offers a slightly different opinion as to what brought about the separation of Church and State in the Constitution. His view concerns the nature of doing good. According to Wood, the crisis which brought about the need to replace the Articles of Confederation with the Constitution was a crisis not only in politics, but in morals. Wood asserts that American political leaders saw what they perceived to be a decline in public virtue, that is, a decline in doing good for the sake of the common good and instead doing good for the sake of the individual. They witnessed a challenge to the republican ideal of a united citizenry willing to sacrifice individual interests for the greater common good. This decline in virtue threatened the very fabric of republican liberty. What is implied here is that Americans were beginning to shift away from a life of use to the common good, or away from a true love to the neighbor. This calls to mind a portion of Arcana Caelestia which states,

Divine order is for the Lord to flow through the interiors of man to his exteriors, thus through the will of the man into his action. This takes place when the man is in good, that is when he is in the affection of doing good for the sake of good, and not for the sake of himself.27

Wood asserts that the Constitution, with its division and balancing of power, marked a shift in which the government divorced itself from a reliance on popular virtue. Despite this shift, he argues, many Americans continued to believe that the future of the republic depended on popular virtue and public morality. Far from giving up on the collective moral imperative of the American people, religious leaders redefined the way it would be defined and expressed. Instead of being located directly within the institution of representative government, public morality was increasingly defined as a quality of non-political organizational life. Schools and families began to receive greater emphasis as bulwarks of morality and liberty. What emerged from the period, then, was a sense of a moral and virtuous American society distinct from the institutions of government. Established religion might have been separated from the institution of the Federal Government, but religion and morality were still seen as vital to the health of the nation. In fact, many consider America to be at its most religious at this time.28

To return to the question of how the founders viewed the proper place of religion and morality in the new nation, they clearly saw that public virtue, that willingness to surrender to the common good, was vital to the survival of the young Republic. That public virtue came from public morality. And for many, that public morality came from a culture which was religious, a religious culture that the Constitution shifted outside of the proper legislative bounds of the Federal government.

The Writings teach that the quality of civil order depends upon the moral and spiritual life flowing into it. George DeCharms wrote that, "Freedom depends, in the last on character; that is, on self-control from consideration for the good of community. Democracy will only succeed where there is with the people an individual conscience formed by the civil, moral, or spiritual truths."29

We read in True Christian Religion

To love one's country is to do the public safety. A person's country is the neighbor because it is like a parent; for in it he was born, it has nourished and still nourishes him, and continues to protect him as it always has done. People ought to do good to their country from love for it, according to its needs.30

The same number also states,

Those who love their country and render good service to it from good will, after death love the Lord's kingdom, for then that is their country; and those who love the Lord's kingdom love the Lord Himself, because the lord is the All in all things of His kingdom.

The Writings emphasize that a civil-moral life should be grounded in religious convictions which presume spiritual causes. True Christian Religion teaches that the Lord regards a nation according to its use (TCR 799) and it is religion, above all, that gives a people or nation its character. (TCR 813–814)

In this way we can see that the founding fathers were correct in their belief that public virtue and public morality, based in religious principles, was vital for the health and survival of the young republic. Recall the words of the Confederation Congress in setting aside a specific day of Thanksgiving, calling on Americans to "testify their gratitude for his goodness, by a cheerful obedience to his laws, and by promoting, each in his station, and by his influence, the practice of true and undefiled religion, which is the great foundation of public prosperity and national happiness." Recall the words of George Washington when he advised his fellow citizens that religion and morality were the "great pillars of human happiness" and that national morality could not exist "in exclusion of religious principle." The founders believed that for the republic to be strong, each citizen must live a life of use to the common good which stemmed from national morality based in religious principles.

This is clearly supported by the following passage in the Apocalypse Explained.

A life from the love of uses is a life of the love of the public good and of love to the neighbor, and also a life of love to the Lord, for the Lord performs uses to man through man, consequently a life of the love of uses is the spiritual Divine life, and everyone who loves a good use and does it from a love for it is loved by the Lord, and is received with joy by the angels in heaven.

The essence of uses is the public good. With the angels the public good in the most general sense means the good of the entire heaven, in a less general sense the good of the society, and in a particular sense the good of the fellow citizen. But with men the essence of uses in the most general sense is both the spiritual and the civil good of the whole human race, in a less general sense the good of the country, in a particular sense the good of a society, and in an individual sense the good of the fellow citizen; and as these goods constitute the essence of uses, love is their life, since all good is of love and the life is in the love.

. . . This is because no one can be kept by the Lord in love to the neighbor unless he is in some love for the public good; and no one can be in that love unless he is in the love of use for the sake of use, or in the love of use from use, thus from the Lord.31

This undermines Jefferson's belief that public virtue could come solely from study of history and the classics. Virtue and morality do not come from man but from a love of the neighbor, a life of use to the common good, and thus from the Lord. Consider again the words in Divine Love and Wisdom

consider whether you can think analytically concerning any form of government, or any civil law, or moral virtue, or spiritual truth, unless the Divine out of His wisdom flows in through the spiritual world. For myself, I could not and can not.32

The Writings also provide an answer to Jefferson's statement, "it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no God. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg." A person's belief in God and religion affects all of society in their relationship to the common good. It also could cause injury if that particular neighbor enters into government. The Writings teach, "The law which is just ought to be enacted in the realm by persons skilled in the law, wise, and who fear God."33

How then can we apply this to our culture and society today? As the founding fathers believed, public virtue and morality, based on religion, was vital to the survival of the nation. The Writings clearly teach that for a free government to endure, it must rest on a moral basis. The Writings also teach that the Lord regards a nation according to its use and it is religion, above all, that gives a people or nation its distinct character.

George Will recently wrote,

Government cannot revise culture, wholesale, but government has— it cannot help but have—cultural consequences. Thus those people who say government should be judged solely by its laws and economic policies, and not at all by its embodiment of morality and its example of personal conduct, do not understand the primacy of culture as a determinant of social health.34

Our civic life can not be morally and spiritually neutral. As Benjamin Franklin said, "The longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth— that God governs in the Affairs of Men. I also believe that without his concurring Aid, we shall succeed in this political building no better than the builders of Babel."

When considering our culture today, when we look to our past for legitimacy, we should remember the vital role that our Founders believed public liberty, public virtue, morality and religion played in the very survival of their young republic. We should also remember that,

When the good of the neighbor, the common good, the good of the Church and of the Lord's kingdom is the end in view, a person's soul is in the Lord's kingdom and so abides with the Lord.35

We must strive for a return of public virtue and morality, a return to the public good, in our society. According to the Writings, this must be accompanied by the restoration of religion as a force in society. As we have seen, many of the founding fathers understood this. Religion cannot be "something that thoroughly enlightened modern people find obnoxious, and from which the public must be protected."

The question could be asked, if a religious and moral culture are so vital to the health of the nation, as both the founding fathers and the Writings tell us, can, or should the government legislate morality? We have seen that the Confederation government thought so, at least to some degree. According to some theories regarding the Constitution, the founders thought the authority to legislate religion, while not proper to the federal government, did rest at the state level. The question we are left with is how to best ensure a return of religion, and thus public virtue, public morality, and the common good to our society. We must remind ourselves of the crucial role our founders saw such a culture playing in the very survival of our republic. When thinking of the importance of the public good and the proper order of society and of government, we should keep in mind the teachings we have been given in the Writings.

I spoke with the angels cogitatively concerning the common good, to the effect that he who, in the life of the body, is for the common good, is also for the common good in the other life; the common good in the other life is the kingdom of the Lord; and thus is he for the kingdom of the Lord, consequently for the Lord himself, who is the all in all things of His kingdom. Hence, how much zeal any one has in the world for the common good, so much he has for the kingdom of the Lord.36

I leave you again with the words from Divine Love and Wisdom,

Consider whether you can think analytically concerning any form of government, or any civil law, or moral virtue, or spiritual truth, unless the Divine out of His wisdom flows in through the spiritual world. For myself, I could not and can not.37

Footnotes top

1 John F. Wilson, "Religion, Government, and Power in the New American Nation," in Religion and American Politics from the Colonial Period to the 1980s, ed. Mark A. Knoll (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 77.

2 George Will, "Seasonal Litigation" in Newsweek (December 21, 1998), p.78.

3 Walter Orthwein, "One Nation Under God: Applying Spiritual Principles to Civil Order," paper presented at Bryn Athyn College, Fall 1998.

4 Examples drawn from George Will, "Seasonal Litigation" in Newsweek (December 21, 1998), p.78.

5 Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787 (New York, NY: W. W. Norton and Company, 1972), p. 60.

6 Ibid., p. 61.

7 Spiritual Experiences 4046.

8 Apocalypse Explained 1226[7].

9 Congressional Thanksgiving Day Proclamation, October 11, 1782.

10 Rules and Articles, for the Better Government of the Troops of the Twelve United English Colonies of North America, June 30, 1775.

11 Rules and Regulations of the Navy, Article 3, November 28, 1775.

12 Congressional Resolution, September 12, 1782.

13 An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio, 1787.

14 Speech to Constitutional Convention, June 28, 1787. There is some debate as to whether this motion failed due to lack of funds for a minister or for fear that they would appear to the public to be in need of help.

15 Circular to the Chief Executives of the States, June 11, 1783.

16 Washington's Farewell Address, 1796.

17 Divine Love and Wisdom 355.

18 Draft of Washington's Farewell Address, 1796.

19 The term "nursing fathers" was drawn from Isaiah 49:23, in which Isaiah commanded that "kings shall be thy nursing fathers, and their queens thy nursing mothers." From the time of the Reformation the responsibilities of the state were understood to be comprehensive, including imposing the church's doctrine on society. The term "nursing father" was used throughout the American colonies with respect to the responsibilities of established churches.

20 The Bill of Rights of the Massachusetts Constitution, Article Three, 1780.

21 Petition to the Virginia General Assembly, from Surrey County, Virginia, November 14, 1785.

22 George Washington to George Mason, October 3, 1785.

23 Richard Henry Lee to James Madison, November 26, 1784.

24 Thomas Jefferson, French Treaties Opinion, 1793.

25 Isaac Kramnick, The Portable Enlightenment Reader (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1995), p. xii.

26 For a full discussion of these views see John F. Wilson, "Religion, Government, and Power in the New American Nation," in Religion and American Politics from the Colonial Period to the 1980s, ed. Mark A. Knoll (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1990), pp. 77–89.

27 Arcana Caelestia 8513.

28 For a full reading of Wood's argument see Gordon S. Wood, "Religion and the American Revolution," in New Directions in American Religious History, ed. Harry S. Stout and D. G. Hart (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1997), pp. 173–198.

29 George DeCharms, Principles of Government (Bryn Athyn, PA: The Academy Book Room, 1960), p. 58.

30 True Christian Religion 414.

31 Apocalypse Explained 1226[6,7].

32 Divine Love and Wisdom 355.

33 Doctrine of Charity 163.

34 George Will, "The Primacy of Culture," in Newsweek (January 18, 1999), p. 64.

35 Arcana Caelestia 3796[4].

36 Spiritual Experiences 4433.

37 Divine Love and Wisdom 355.